Neurorhetorics is an important field that emerged in an era when the “global mental health crisis” prevailed worldwide (Gruber et al., 2024). Understanding the brain has been deeply embedded in social problems (Gruber et al., 2024; Jack, 2010; Graham, 2009), social media (Thornton, 2011), popular culture (Gibbons, 2014; Thornton, 2011), and interdisciplinary studies (Gruber et al., 2024; Jewel, 2016; Mays & Jung, 2012). As Gruber points out the high exigency of neurorhetoric in an important forum in Rhetorical Society Quarterly, “Examinations of cognition and the brain pop up tactically and discursively around so many contemporary cultural crises that rhetorical scholars hope to understand better and confront.” (Gruber et al., 2024, p. 382)

In this subfield report, I will first overview the field of neurorhetorics, providing the origin and the main themes of neurorhetorics. Then, I will specifically dive into the topic of brain images, the most frequent artifacts in neurorhetoric studies, and neurodiversity, one of the most important divisions under the discussion of neurorhetorics, which broadens the understanding of both neurorhetorics and neuroscience (Jack, 2010; Jack & Appelbaum, 2010).

The Origin of Neurorhetorics

The early discussion of the rhetoric of the brain can be traced back to 1988. From the late 1980s to the 2010s, scholars’ discussions about rhetoric and the understanding of the brain are related to the popular understanding of the function of the brain, such as the overuse of the I.Q. concept to explain poor academic performance, which is still prevailing today (Rose, 1988) and the emphasis on the rationality of “left-half” of the brain (Walker, 1990).

There weren’t systematic discussions using “neurorhetorics” as terminology until 2010, when the Rhetorical Society Quarterly published a special issue about neurorhetorics, and Jordynn Jack (2010) published the article, “What are Neurorhetorics.” According to Jack, the origin story of neurorhetorics began with the collaboration between the rhetorician and neuroscientist when Appelbaum, the neuroscientist, raised the controversy of fMRI research: the statistical significance might be incorrectly found due to happenstance (Gruber et al., 2024. p. 399).

Because of the collaboration, they identified the key approaches and illustrated neurorhetorics as a systematic research field. Aiming at broader questions between neuroscience and rhetorics, they collaboratively published the article “This is Your Brain on Rhetoric:” Research Directions for Neurorhetorics. (Jack & Appelbaum, 2010) This article first introduced the “Two-sided approaches” to studying Neurorhetoric: use neuroscience to expand the rhetorical theory and study the Rhetoric of neuroscience. For the former, they raised how impaired communication of Neurodiversity can expand the understanding of rhetoric. For the latter, they study the report, discussion, and social media engagement that neuroscience functions.

Four Main Themes in Neurorhetorics

Under the topic of neurodiversity, Jack and Appelbaum (2010) investigated why empathy has been chosen as the most common research topic: the concept “empathy” is “operational” and fits the interest of the scientists. The consequence includes pushing the normative to the autism community and causing “dehumanization” since autism are labeled as having a “lack of empathy,” which reduces their rhetorical ability. This phenomenon has been further discussed and framed as “neuroessentialism,” which reduces a complicated concept into what fits the needs of scientific methods, like fMRI machine (Jack, 2019, p. 41)

The discussion of neurorhetoric has developed between 2010 and 2024. In 2024, Gruber (2024) summarized four consistent themes based on Jack’s approaches:

- Applications of Neuroscience to Rhetoric: These studies expand the understanding of rhetorics through the concepts or assumptions of neuroscience, first recommended by Jack (2010);

- Critiques of Neuroreductionism: These studies analyze and critique the case that reduced complicated concepts into operational concepts;

- Critiques of Neuroinflationism: The studies about neuroinflationism mainly discussed how the neuroscience concepts are used as exaggerations and miscommunications;

- Critiques of Neuroassimilation: Rhetorician scholars examine how the brain science concepts are used as evidence to legitimatize the conclusion. In the last decade, the discussion about neurorhetorics has accumulated, and many researchers contributed important insight into topics from different perspectives, which has been summarized as the four main themes Gruber provided.

I summarized the main literature under each theme below:

- For the Applications of Neuroscience to Rhetoric, Mays and Jung (2012) discussed this theme and developed the methodology of neurorhetoric. Under the background that neuroscience had been popular and educators were “suddenly interested in” brain research in 2011, they provided a critique of the discussion between the language and the mind at the time, such as George Lakoff’s usage of brain science to improve authority. Building on their critique, they raised “terministic inquiry” as the methodology of neurorhetoric, claiming that researchers should see the terminology overlap between neuroscience and rhetoric and the need for rhetoric that reminds the researchers “how much we don’t know about how the brain “really” works.” They also raised two concepts for this method: Agency and learning when conducting the research.

- Many researchers provided Critiques of Neuroreductionism, from the early criticism of I.Q. overuse (Rose, 1988) to the observation of the frequent studies of empathy in neuroscience studies of autism (Jack & Appelbaum, 2010). Recently, Jack’s (2019) book, Raveling the Brain, provides a persuasive case study of an fMRI research on creativity and argues that neuroscience research can oversimplify the concepts that have rich nuance. In the title of this book, she uses “raveling” as the rhetoric that is opposite to the common word used in neuroscience articles: “unraveling.” By raising this contrast, she points out that neuroscience tends to oversimplify the problem and make promises using scientific tools. She uses the example of how neuroscientists study the creativity of freestyle rappers using fMRI techniques to show how they establish neuroessentialism: neuroscientists operationalized creativity to fit the fMRI machine and created the contrast between “creativity (Invention)” and “Imitation (Mimesis).” However, Jack argued that creativity is, in fact, derived from imitation. Her critique roots the contemporary understanding of creativity into the rhetorical tradition, making the understanding deeper and showing how Neuroreductionism can lose the rich dimensions of one concept.

- The theme of Neuroinflationism is more about the prevailing opinion, “I’m my brain,” which exaggerates the priority of the brain. Thornton (2011) provides a systematic critique for this problem in her book, Brain Culture: Neuroscience and Popular Media. She pointed out that while society appeals to the brain to find the solutions to every problem, the wider impact on child development, family life, education, and public policy happens and causes negative consequences. For example, she raised George H.W. Bush’s “Decade of the Brain” in 1990 as an example to discuss how the government’s investment into neuroscience can embody this opinion. Through the rhetorical analysis of how the social discourse of neural correlates of concepts such as pathos, presence, or identification, the author also reveals how imaging technology served as a persuasive language to the self-help discourse and popular neuroscience.

- For critiques of Neuroassimilation, Gruber explains it as the examination of “the tactical use of brain science as evidence to enhance the appeal of a position or gain legitimacy.” She raises Gibbons’s “Beliefs about the Mind as Doxastic Inventional Resource” as an example: a rhetorical study about the most famous child-rearing manual, The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care by Dr. Benjamin Spock. This book claimed to use concepts of Freud in the first edition to gain legitimacy. However, Dr. Spock admitted that the Freudian concepts did not actually guide the principles in the book; he just used them to bring out practical guidance. Even in this situation, the manual still gained much success. In Gibbon’s analysis, it is the mind-related doxa that “across texts and contexts” implicitly builds the authority. This article revealed how the beliefs of the mind (mind-related doxa) could shape peoples’ understanding and guide our everyday lives, providing insight into how neurostimulation works in the communication between the scientific community and the public. In this process, besides Gibbon’s example, the studies about brain images should also apply to the concept of neuroassimilation, which is also a kind of important artifact that impacts people’s mind-related doxa.

The Brain Images as the Artifact of Neurorhetorics

Brain images play a pivotal role in investigating neurorhetorics since much neurological evidence is shown as brain-scanning pictures like fMRI, PET, EGG, etc. According to the current research, brain images build identification rhetorically, enhance agency, and increase credibility.

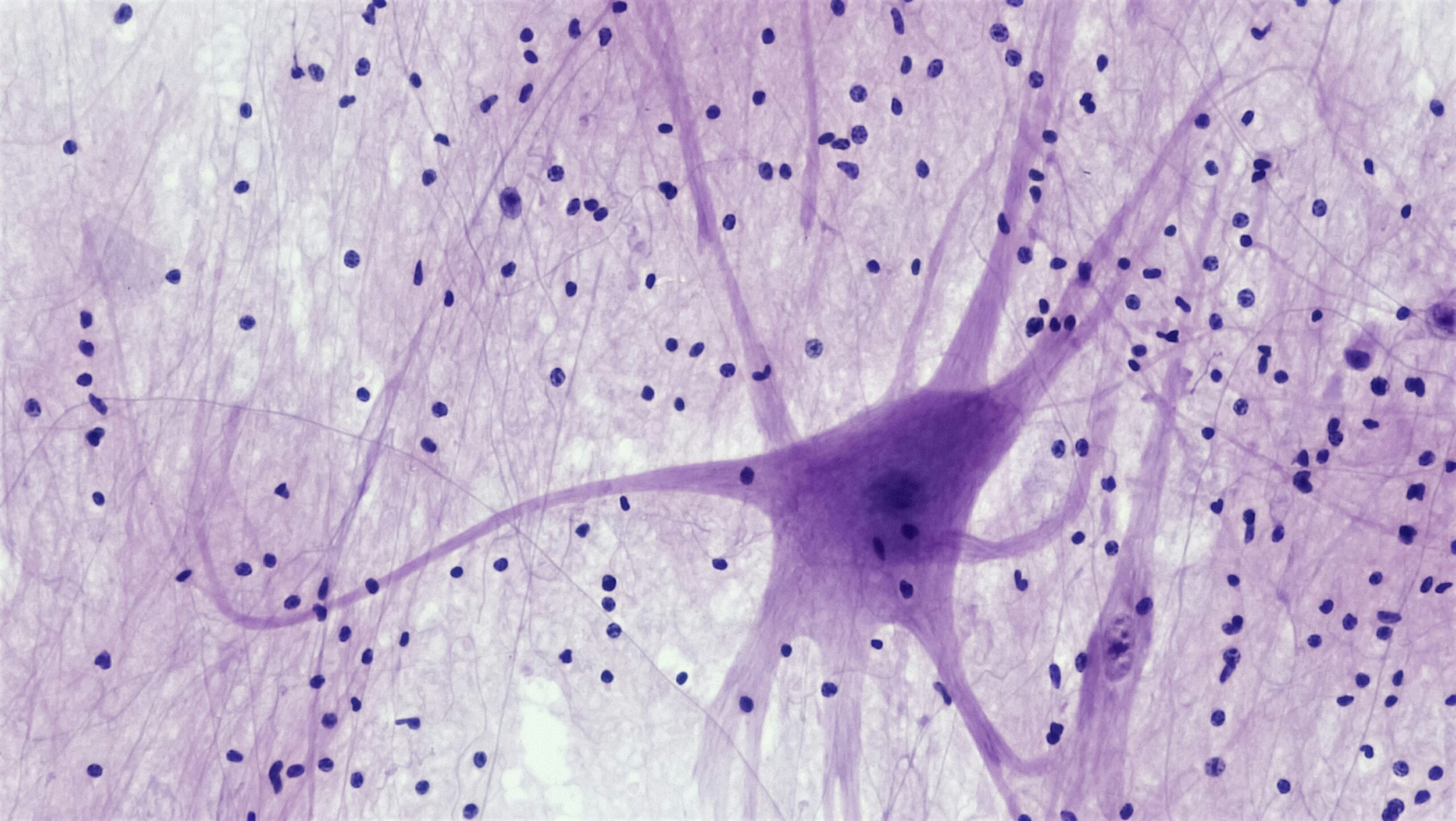

Early in 2004, Joseph Dumit (2004) conducted an ethnographic study in a PET scanning laboratory to investigate how the PET brain images work. In his book, he argued that the brain images that label mental health patients (like ADHD) and “normal” people can overreact to the problem and lead to misunderstanding (p.155, see figure 1). He introduced Kenneth Burke’s idea of identification and related the culture that divides the “normal” and “abnormal” to the brain images that depict the difference between the normal brain and the ADHD brain: “This notion of self-persuasion (of identification) helps us keep in mind both the persuasive action of received facts (e.g., from a magazine) and the form in which we often (but not always) incorporate them as facts.” (7).

Figure 1. Chosen from Dumit (2004), showcasing the PET brain image that compares the brain of ADHD and the normal control subject.

Moreover, Graham (2009) provides another ethnography about the rhetoric of medicine. This article studied “how non-human agents (Brain scan) contributed to fibromyalgia’s acceptance within the highly regulated discourses of western biomedicine.” This article provides a new perspective on the rhetorical theory of agency through an in-depth ontological analysis of the rhetoric of PET scanning pictures, articulating how it helps fibromyalgia be persuasive and get approval from The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

How brain images build credibility has also been widely studied. For example, McCabe and Castel (2008)reported several pieces of research about brain images, concluding that they “lend support to the notion” of credibility and trace investigated these brain images can provide a physical basis for abstract cognitive processes and lead to neuroreductionism. Similar studies like Gibbons (2007), Jack, et al. (2017) Rothfelder & Thornton (2017) also cover this topic.

While the rhetorics of brain images seem to increase the persuasion, the oversimplification of complicated facts and the effect of naturalizing the social classification are also discussed deeply by rhetoricians.

(Neuro)Rhetorics and Neurodiversity

Neurodiversity is an important topic in neurorhetorics. Through the lens of neurorhetorics, the exigent issues in neurodiversity include gender, race, humanization, and emotion.

The term “neurodiversity” was credited to an Australian sociologist, Judy Singer. It is an umbrella term describing neurodevelopmental handicaps such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or dyslexia, etc. The purpose of raising the term is to provide an alternative way to indicate the people without focusing on the deficit of the people; instead, the term focuses on the spectrum view of human beings. Judy Singer investigated the word usage regarding disability from the perspective of social construction, focusing on how language shapes the social attitude toward people: “It was neuroscience that legitimated us, and it was the language of neuroscience and computer science that was the source of empowering metaphors for our movement. I ventured a critique of these tendencies in my thesis in the section titled Social constructionism vs biological determinism.” (Singer, 2016, p. 13)

Therefore, the activism of neurodiversity could be recognized as a rhetorical event. In a recent chapter of Rhetoric Social Quarterly, neurorhetoric was raised as an emerging field, and a wide range of topics about neurorhetoric should be discussed. In A Forum on Neurorhetorics: Conscious of the Past, Mindful of the Future, Gruber et.al summarized the research field of neurodiversity from the lens of rhetoric:

For the most part, in rhetorical studies, I think we mostly avoided simple adoption of neuroscience and instead took a different path more in keeping with traditional approaches to rhetorical history: case studies, analyses of popular, scientific, and other kinds of texts; and especially, with the growth of Rhetoric of Health and Medicine, a concern with disability, neurodiversity, and mental health.” (Gruber et.al, 2024, p. 400).

With this trend, it is worth taking a closer look at the field of neurodiversity and rhetoric. Among the rhetorical research on neurodiversity, there are three main themes:

1) Language. Including neurorhetoric broadly and focusing on the intersection of neurorhetoric and neurodiversity. Among these areas, questions like the history of the language of neurodiversity and how it provides different insights as social activism were investigated by literature from various areas. Specifically, the language about the gender stereotype of autism: “The Extreme Male Brain,” has been widely discussed in the main rhetorical studies of neurodiversity (Yergeau, 2018; Jack, 2014, 2011).

2) The different perceptions from normative. For example, the concept of “crip time” can mark a different lived experience from the social agenda. “Crip time” is the time perception that “we live our lives with a flexible approach to normative time frames” like work schedules, deadlines, or even just waking and sleeping.” (Samuels, 2017). The crip time is a perception issue related to social agenda, self-identity, etc. Another main aspect is about the “emotional dysregulation.” From the perspective of neuroscience, emotion is related to not only perception itself but also a mechanism that is related to the interoception that predicts the surroundings of human beings. When neurodivergent people have different interoception, they always show different patterns of emotions. However, from the lens of neurorhetorics, the discussion of neurodivergent people’s emotions is narrowed down to the flatland that fits the scientific discourse, while the real situation deserves further investigation (Gross, 2008).

(3) Social activism. Neurodiversity is also an issue highly related to social activism. The most influential book is Yergeau’s (2018) “Authoring Autism,” which discusses the (de)humanization of autism, claiming that autism’s rhetorical ability should be recognized. Traditionally, autism is seen as the “less humanized” since the current media focuses on their impairment. The author challenged the Theory of Mind (ToM), which is a prevailing neuroscience concept arguing that people can somehow know other people’s thoughts because people have some common ground. Yergeau opposes the idea that the autistic person lacks ToM, which can restrain autism’s rhetorical ability and dehumanize autism. Rather, they cannot do that because neurotypical people define intentions, which is different from neurodivergent people. Furthermore, the author also challenged the viability of the ToM itself. This is also related to pushing the “formative” to the neurodiversity people in a neurorhetoric way.

While the activism of Yergeau can be easily understood as claiming that autism is not a person with a disability, I would say resisting dehumanization is not equal to resist to be seen as disabled and refusing support.

Conclusion

Neurorhetorics is a subfield with many possibilities and varieties. In the age of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI,) which is built on the Large Language Model (LLM) and relies on neural networks, people’s understanding of the brain has been changing fast. Looking forward, Jack indicated a wide range of future research topics of neurorhetorics, including the visual studies of brain images and the historic discourse of ADHD. In my mind, how the rhetorics of embodied cognition changed since the emergence of GenAI can be also a future direction.

Reference

Dumit, J. (2021). Picturing Personhood: Brain Scans and Biomedical Identity. Princeton University Press.

Gibbons, M. G. (2007). Seeing the mind in the matter: Functional brain imaging as framed visual argument. Argumentation and Advocacy, 43(3–4), 175–189.

Gibbons, M. G. (2014). Beliefs about the Mind as Doxastic Inventional Resource: Freud, Neuroscience, and the Case of Dr. Spock’s Baby and Child Care. Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 44(5), 427–448.

Graham, S. S. (2009). Agency and the Rhetoric of Medicine: Biomedical Brain Scans and the Ontology of Fibromyalgia. Technical Communication Quarterly, 18(4), 376–404.

Gross, D. M. (2008). The Secret History of Emotion: From Aristotle’s Rhetoric to Modern Brain Science. University of Chicago Press.

Gruber, D. R., Anderson, W. K. Z., Gibbons, M., Jack, J., Mays, C., Snelling, T., Welsh, P., & Wilson, E. (2024). A Forum on Neurorhetorics: Conscious of the Past, Mindful of the Future. Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 54(4), 381–404.

Jack, J. (2010). What are Neurorhetorics? Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 40(5), 405–410.

Jack, J. (2011). “The Extreme Male Brain?” Incrementum and the Rhetorical Gendering of

Jack, J. (2014). Autism and Gender: From Refrigerator Mothers to Computer Geeks. University of Illinois Press.

Jack, J. (2019). Raveling the Brain: Toward a Transdisciplinary Neurorhetoric. Ohio State University Press.

Jack, J., & Appelbaum, L. G. (2010). “This is Your Brain on Rhetoric”: Research Directions for Neurorhetorics. Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 40(5), 411–437.

Jack, J., Appelbaum, L. G., Beam, E., Moody, J., & Huettel, S. A. (2017). Mapping Rhetorical Topologies in Cognitive Neuroscience. In L. Walsh & C. Boyle (Eds.), Topologies as Techniques for a Post-Critical Rhetoric (pp. 125–150). Springer International Publishing.

Jewel, L. (2016). Neurorhetoric, Race, and the Law: Toxic Neural Pathways and Healing Alternatives. Md. L. Rev., 76, 663.

Mays, C., & Jung, J. (2012). Priming Terministic Inquiry: Toward a Methodology of Neurorhetoric. Rhetoric Review, 31(1), 41–59.

McCabe, D. P., & Castel, A. D. (2008). Seeing is believing: The effect of brain images on judgments of scientific reasoning. Cognition, 107(1), 343–352.

Rose, M. (1988). Narrowing the Mind and Page: Remedial Writers and Cognitive Reductionism. College Composition & Communication, 39(3), 267–302.

Rothfelder, K., & Thornton, D. J. (2017). Man Interrupted: Mental Illness Narrative as a Rhetoric of Proximity. Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 47(4), 359–382.

Samuels, E. (2017). Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time. Disability Studies Quarterly, 37(3), Article 3.

Thornton, D. J. (2011). Brain Culture: Neuroscience and Popular Media. Rutgers University Press.

Walker, J. (1990). Of Brains and Rhetorics. College English, 52(3), 301–322.

Yergeau, M. R. (2018). Authoring Autism: On Rhetoric and Neurological Queerness. Duke University Press.

Leave a Reply