* Report for the research project, Visual Study of Historic District in Huizhou: A Visual Ethnography Perspective

* Principal Investigator: Daocheng Lin, Participator: Dr. Ziyao Huang, Dr. Jiawei Xu, Ms. Yixuan Xie

Overview

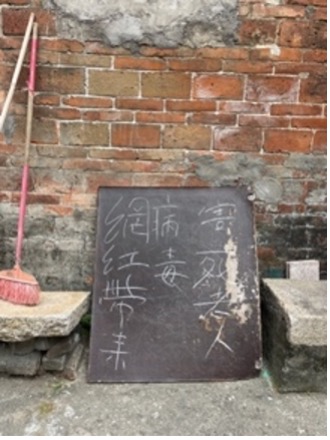

As a historical and cultural city in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, Huizhou in Guangdong Province has a large number of historic districts. Over the past two decades, the state-led urban conservation practice has dominated the urban renewal process, and the rapid renewal of the cities has led to the problem of urban sprawl. Recently, the cultural-led regeneration among historic districts has dominated urban renewal to drive the economy (Mai et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2017) and retain sustainability (Lin et al., 2014). However, when many retailers rented the stores, utilized the influence of wanghong (internet celebrity) culture (Zhang et al., 2022), and introduced cultural merchandise into historic districts, the historic districts were symbolized as a place of nostalgia because of the distribution of social media (Figure 1). I noticed that there were certain residents explicitly resisted the renewals. For example, a resident living in a historic district in Foshan put a chalkboard outside his house and wrote, “Wanghong (Internet celebrity) has brought virus and kill the elder” (Figure 1), which may indicate that the residents in historic districts resist latest digital media trend and commercial-led renewal of the historic and they used certain strategy to express the resistance or maintain their lifestyle. This conflict between newly developed digital culture toward urban space in China and older traditional culture in historic districts has raised the need for nuance investigation into the everyday life of the residents of historic districts.

Figure 1 A photo shot at Yuangang District, Foshan, Daocheng Lin, 2023. Left: the nostalgic symbols in the historic district; Right: The hate speech on the chalkboard.

To reveal the nuance of everyday life intertwined with urbanization, this project was concerned with everyday practice in the historic districts in Huizhou. The project focused on the questions below:

RQ1. How do the renewals of historic districts shape the daily lives of their residents?

RQ2. Facing the conflict between older everyday life and urbanization in Greater Bay Areas, how do residents use everyday strategies?

To address these questions, we have conducted a practice-led study and took Beimen Street as a place of fieldwork. From a perspective of everyday practices raised by Michel de Certeau, we emphasized the sensory aspect of everyday life and adopted walking as a research method to address the questions. Further, we also used drawing as a way of exploring as well as photos.

This study argues that “miscellany” is the major practice of the residents living in historic districts, no matter whether they are passively involved or actively using it. Unlike living in more newly developed communities, residents have a more flexible and miscellaneous way of mixing and matching sites and objects from their daily lives to meet their own needs for safety and community relations. We depicted this miscellany strategy on the aspects of place, residents, and culture: (1) we discovered that “semi-enclosed pattern” and “narrow alleys” in the building of the historic districts were brought about by active and passive community renewal; (2) residents of historic districts often use “miscellany” as a daily life strategy, such as “the use of doorways”, “the opening of the first floor”, and “rooftop agriculture”, which reflect their miscellany of space use; (3) The cultural symbols of the historic district present miscellaneous styles, including the dialogues between institutional and youth cultures, and the dialogues between foreign and traditional cultures.

The outline of this report includes (i) the background of the study, (ii) the research design, (iii) three aspects of everyday practice in Beimen Street: places, residents, and culture, (iv) conclusion.

i. Background of the Study

State-Led Political Understanding of Historic Districts in China: The concept of “historic districts” in China is not only an academic terminology but also a reflection of the top-down management of historic districts. The government identifies particular urban areas as “Historical and Cultural districts” (历史文化街区) and compiles official files to design the policies (Historic District Conservation Office in Huizhou, 2017a). The term first appeared in the 2002 Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Cultural Relics and is specifically defined in the document “Planning Standards for the Protection of Historical and Cultural Names (GB/T50357-2018)”: historical and cultural areas that are particularly rich in preserved cultural relics, have a concentration of historical buildings, are able to more completely and authentically embody the traditional pattern and historical style, and have a certain scale of historical locations, which are designated for publication by the people’s governments of provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities directly under the central government.

Therefore, the government’s understanding of historic districts represents the policy aspects of the renewal of those historic district areas and can be important background information to understanding how governmental policies shape residents’ everyday lives.

Conflicts between Old and New: While the large-scale demolition happened in historic districts, the intrinsic nature of a large amount of architecture has been destroyed (Zhang et al., 2017; Gong & Zhong, 2015). Take Shuidong Street in Huizhou as an example, after its large-scale demolition led by the government in 2014, the residents in the old district moved and the newly built commercial hall was built. Yang (2021) has critically investigated the authenticity of Shuidong Street, complaining that “Nonetheless, the over-emphasis on the physical architectural appearance and commodification of regional culture indicates that the national-level authenticity guidelines are adopted not for pure conservation purposes but to serve the local government’s political agendas, which reflects the disconnection between conservation ideologies and bureaucratic realities”.

The conflicts are common in urban renewal in Huizhou. With high-rise buildings rising from the ground and a high degree of urbanization, this has led to radical changes in people’s everyday lives compared with those in the past. So far, according to the official credentials from the local government, Huizhou City has 6 official historic districts: Beimen Street, Jindai Street, Shuidong Street, Iron Furnace Lake, Danshui Old Town, and Pinghai Cross Street (Historic District Conservation Office in Huizhou, 2017b). These historic districts are under certain protection, maintenance, and renewal policies, yet, the conflicts between these policies and the well-being of the residents still exist: during the executive process of the policies, the infrastructure has taken on extremely diverse patterns and forms in line with the rapid changes and different directions of development of the city, and also contain rich cultural resources as a result of the intertwining of cultures in the Greater Bay Area, which is predominantly Cantonese, Hakka and Chaoshan cultures.

The public has been deeply concerned about this conflict between the old lifestyle and the newly developed city. Because of a significant slowdown in the trend of “large-scale demolition and construction” in historic districts, China’s government has raised the development strategy and has inevitably shifted to the direction of “gradual renewal instead of demolition” (Zhang et al., 2017; Gong & Zhong, 2015) to maintain cultural heritage as well as sustainability. Based on this background, scholars have investigated the topics from different perspectives.

Recent Research about Historic Districts in China: The studies about historic districts in China are highly interdisciplinary. The mainstream studies are concerned with the historical aspects of historic streets, spatial aspects intertwining with cultural and commercial space, and urban renewal strategies (Fan, 2020; Huang, 2020). Recently, there is a trend that raises the importance of everyday practice aspects (Zhang & Liu, 2019; Guo, 2014; Chen, 2014).

From a review of the existing literature, it is clear that historic districts can be understood not only in terms of spatial scale, architectural form, or economic indicators, but also in terms of the daily lives of the inhabitants, production relations, and “living” cultural forms that are difficult to quantify (Butler et al., 2022; Cho et al., 2022; Borer, 2006). Since the emergence of the “social” turn in human geography, the study of the “daily life” of the residents of historic districts has increasingly become a topic of discussion (Guo, 2014; Gauthier & Taaffe, 2002). Discussions of everyday life are conducted either within the framework of time geography, where researchers often use questionnaires to collect the paths of daily activities of specific groups of people within a space, or from the perspective of spatial relations of production, where researchers often conduct mixed studies consisting of questionnaires, in-depth interviews, and other methods in order to model and explain the relations of production involved in a particular place (Hägerstrand, 1985; Jiang et al., 2022). Research in architectural anthropology, on the other hand, using photographs, collages, and other forms of documentation so as to provide in-depth depictions of specific subjects (Pink, 2021; Luminais, 2015), such as a related Danish study that explored the possibilities of collage as a method of research, which targeted homeless people and encouraged respondents to depict, in the form of a collage, the paths, experiences, and props of their own day-to-day activities to present their own lifeworlds (Stender et al., 2021, 76-89); and Japanese architectural anthropology has also been more involved with visual means of documentation, especially hand-painting, which, in the name of modernology (“考现学”), addresses the details of residents’ daily lives and often yields surprising conclusions (Wang et al., 2018).

In the discussion on the studies focus on everyday life aspects, how the research data are collected and the position of the researcher in the whole study are also the key concerns. Mobility is considered one of the most important attributes of urban sociology in the discussion of urban sociology (Shortell & Brown, 2016), and in the study of the mobility of urban people, “walking” is an important activity in the daily life of the city, and an important activity in the daily life of the city. Walking is one of the most important activities in daily life and an important methodology adopted by scholars (O’Neill & Roberts, 2019; Yi’En, 2014; Pink et al., 2010). There is a long history of paying attention to walking and utilizing walking as a research method, but nowadays, the theoretical basis of walking is mainly situationist theory, which believes that the current concepts of the mode of production, productivity, and production relations are beginning to be replaced by the landscape, space, and daily life (Shortell & Brown, 2016, 110-111), and the main scholars who represent this theory are Guy-Ernest Debord and Raoul Vaneigem among others.

Within the framework of the Situationist discourse, the notion of walking has been divided into two categories: Flâneur and Dérive (drifting), “visiting the city as an outsider, as a spectator, detached from the relations of production in the city” (Shortell & Brown, 2016, 110), “detaching oneself from the shackles of everyday life and allowing chance encounters to guide one’s steps”. The other is “Dérive”, “to break away from the shackles of everyday life and to let chance encounters guide one’s steps”.

Research using the “walking” method often employs ethnographic accounts of the walks, while visual materials such as photographs and videos are also emphasized. “Visuals have a more important place in the walking method, and visual materials such as photographs and videos are considered to be “more intimate and reciprocal” than words (Shortell & Brown, 2016, 250).

Walking as a research method focuses on everyday aspects of the socio-spatial aspect of the city (Yi’En, 2014), although some studies also admitted the constraints and limitations of the research (Shortell & Brown, 2016, 187). Walking ethnography method can provide specific and detailed data, however, due to human and resource constraints, it is not possible to cover the entirety of the city using the walking method, and the problem of researcher’s bias and subjectivity, which is hard to avoid. Nonetheless, walking, like other types of ethnographic research, as a specific (idiographic) study, can still broaden the breadth and richness of our knowledge of historic districts.

ii. Research Design

We conducted an exploratory study using the ethnographic research method of “walking” as the object of the daily life of the inhabitants of the historic district. In this study, the researcher will choose the type of “Dérive” or “Wander” to explore the historic district by following episodic daily events and interactions.

In conducting the research, this study will incorporate Michel de Certeau’s theory of the practices of everyday life for the construction of the conceptual framework. According to Certeau (2011, 30-31), the practical behavior of daily life in the production-consumption relationship, common people through the daily activities of the use of the product behavior, can be dynamic in the reproduction of the meaning of the product. Therefore, to understand the spatial shaping of daily life behaviors, it is necessary to examine the allocation behaviors of residents towards buildings, structures, and daily necessities in historic districts. Among them, the tactics of everyday life occupy an important position in the structured investigation of everyday practices, which Certeau considers as “trivial and temporal”, through which ordinary people can manipulate the course of events, thus engaging in dynamic dialogues with various social parties and achieving a steady state of power relations (Certeau, 2011, xxiii).

In this study, the descriptive theories were established from the level of everyday strategies of inhabitants on Beimen Street by adopting walking ethnography and its artistic experiment. Revealing the relationship between historic districts and residents’ daily lives. This study will focus on the daily lives of the residents in the process of data collection, and will trace and refine the impact of the historic district environment from these daily lives;

Research process: This study utilizes walking ethnographic research and focus on the places and its intertwined with everyday practice of residents. Given the scale of this project, one of the officially recognized historical and cultural neighborhoods in Huizhou City, Beimen Street, was chosen for this study.

Ultimately, this study followed the following process:

Step 1: Preparation

Internet data collection: Collection of literature, reports, current affairs discussions, advertising campaigns, etc. on “Beimen Street”;

Step 2: Field visits

First fieldwork: During the first fieldwork, the researcher accumulated visual and sensory materials, mainly through the use of cameras and written field notes. In the course of the study, the researcher took the theme of “everyday life” as a guideline and conducted a walking study. Focusing on the body language, actions, and conversations of the residents, as well as the characteristics of the buildings on the site, their use, and transportation, the researcher took photographs while writing down field notes, and marked the route of the first visit on a map using a GPS positioning device.

Second Fieldwork: In the second field trip, the researcher will conduct a walking study mainly utilizing sketchbooks for the exploration of drawing as a method. While sketching, the textual part of the field notes will be combined with the drawn sketches graphically. During the process, the GPS positioning device is still utilized to mark the route of the second expedition on the map.

Step 3: Data Analysis

Once the visual and field notes data were collected, the researcher combined the thematic research approach by coding the resulting data using the software Atlas.ti and organizing and summarizing the features and themes in relation to the research questions and daily life practice perspectives.

III. Daily life in historic districts

3.1 Overview of the Beimen Street Historic District

Beimen Street was built according to Huizhou’s Mount Bengshan, with an area of 5.1 hectares. The history of Beimenjie can be traced back to the Sui Dynasty (591), and it is the seat of the prefectures of successive dynasties, which has an important historical status. Beimen Street was evaluated as a “Provincial Historical and Cultural District”, from Beimenjie 2 Lane in the west to Binjiang West Road in the east, Zhongshan Park in the south to the south of Huizhou Kandi Hotel in the north, and has a number of protected cultural relics, buildings, and pagodas, such as Ming and Qing Dynasty Old City Walls, Zhongshan Memorial Hall, Wangye Pavilion, Miao House, etc.

Due to the various living statuses of the inhabitants, Beimen Street is also an ideal place to study the daily life practices of the residents of the historic district. There are a total of 20 historic buildings on Beimen Street in Huizhou City, embedded among the residential houses of the inhabitants. Besides, most of the residential houses remain and haven’t been demolished and rebuilt, unlike Shuidong Street in the same city. Therefore, Beimen Street is an ideal place for observation of the conflicts between the old lifestyle of the inhabitants and the rapid development of urban cities.

3.2 Beimen Street as a place of daily life

The unique architecture of Beimen Street, which is also a place where residents live and interact with each other on a daily basis, is the starting point for the investigations conducted in this study. According to Duan Yifu, a humanistic geographer, a place is a place where people make perceptions based on specific objects in the environment (Tuan, 2001, 3). Places are not only architectural monoliths constructed of masonry, but also contain a wealth of life details, emotions and cultural meanings.

In walking ethnography, investigations are often carried out with visual elements (visible) as the main focus. Walking ethnography provides a way of interpreting the visual by placing it under the perspective of social practice (O’Neill & Roberts, 2019, 26). In order to reveal the characteristics of Beimenjie as a place of daily life, this study looks at the visible architectural patterns, building materials and building components.

(1) Architectural pattern of Beimen Street

In the course of the walking study, the researcher found that there are two types of architectural patterns that are visually representative, namely the “semi-enclosed pattern” and the “narrow alley” (see Table 2). The “semi-enclosed pattern” is a courtyard-like structure in the middle of the three houses, where the middle house has a slightly greater depth and then forms a courtyard in the middle. The “semi-enclosed structure” serves as a substitute for the “courtyard” in the daily life of the residents. Such a space is often used as a public travel place, and thus parking of e-bikes and other means of transportation serves as a buffer for residents in their travels. In the researcher’s observation, the courtyard-like structure formed by the “semi-enclosed pattern” was also used by children as a playground:

“I met a child, hovering out of a compound of half-enclosed structures on Wuyi Road, with a box over his head, walking briskly and quickly down the street until he reached Zhongshan Park, where he got into the box himself and played until he met a young friend who summoned him to a game of badminton.”

Table 1: Semi-enclosed pattern and narrow alleys

| semicircular pattern |  |

| narrow street |  |

Therefore, the role played by the semi-enclosed pattern in the daily life of the historic district has a positive significance as a buffer place for the daily life of the residents.

On the other hand, “narrow alleys” are extremely narrow passages with a width of no more than 1 meter. Narrow alleys are uncomfortable and have a negative impact on the daily life of the residents, as light, ventilation, and mobility are all poorer due to narrow alleys.

These narrow alleys had once been a hot topic around 2010. This kind of building is called “shaking-hands building”, which indicates that the distance between the buildings is so narrow that it looks like the buildings are “shaking hands”. A case study indicated that the formation of the shaking-hands buildings involves the conflicts between top-down state-led demolition and the benefits of the residents, in which residents have extended the buildings against the regulations made by states as well as their own coziness of life because they thought that the government exploits their working opportunities as peasants. These actions were explained as “weapons of the weak” that originated from J.C. Sccot by scholars (Li, 2010). In our studies, the phenomenon has also been observed widely:

“Continuing south, not far from the Thai restaurant, there is a very narrow cul-de-sac, with extremely narrow building spacing, and deep within it is the entrance to a residence that has been unoccupied for a long time. The cul-de-sac is bounded on the north by an old residence, and on the south by a large, nine-story, relatively new building, which was created by a question of the sequence of building construction.”

Narrow alleys are created not only between buildings, but also when single buildings are being upgraded (see Figure 2):

Figure 2. Narrow Alley in Front of the Courthouse Street, Daocheng Lin, 2022

“As I walked down Court Street, one of the first buildings that caught my eye was an extremely narrow door. This one mansion door was unusual in that it had some depth and was much narrower than the doors of the other buildings, while the window pattern above it indicated that it was a more dated design. The most likely explanation is that in subsequent remodeling, the storefront next to this door squeezed the space of the original doorway.”

It can be seen that the semi-enclosed pattern has a positive significance to the residents’ daily life, and it is a courtyard space developed by the residents in a dynamic situation; while the situation of narrow alleys is more complicated, the narrow alleys between buildings are often generated by the more primitive community regeneration, and the narrow alleys generated in single buildings are due to the owner’s own spatial planning. The specific reasons for the formation of these alleys will reveal the games and considerations of the residents involved in the dynamic community renewal.

3.3 Everyday life strategies for residents of Beimen Street

The everyday life strategies of residents are the focus of walking ethnography. Everyday life strategies are actions taken by residents in their daily lives and are a form of dialog (Certeau, 2011, xv). After this walking ethnography, this study concludes that door-side utilization, first-floor openness, and agricultural cultivation, are commonly used daily life strategies in Beimen Street, and these daily life strategies are often adopted by local middle-aged and elderly people, which, on the one hand, can maintain the acquaintance society, and on the other hand, directly or indirectly strengthen the sense of security. In the course of the walking study, we observed the paths of the residents’ daily lives. And the use of dialect, the utilization of space, and the traces of agriculture were observed.

(1) Daily life path

Everyday routes are the main object of study in time geography and the theory of everyday life (Zhang & Chai, 2016). However, according to Certeau, simply marking residents’ daily routes on maps does not describe and record residents’ specific activities and a great deal of specific information is lost. Therefore, this study focuses on the residents’ daily routes as well as their body language and action states. Moreover, this study found that shorthand has unique advantages in the depiction of daily life paths.

In the daily life path of children, “play” occupies a large proportion, and their state of action is interacting with the environment with a high density, for example, children who play with the boxes that can be found everywhere in the historic district:

“I met a child, hovering out of a compound of semi-enclosed structures on Wuyi Road, with a box over his head, walking briskly and quickly down the street until he reached Zhongshan Park, where he got into the box himself and played until he met a young friend who summoned him to a game of badminton.”

And in Zhongshan Park, the researcher observed that many elderly plazas were hobbling around with a variety of crutches for activities:

“On the way, I found another subject matter: it is the mobility trajectory of the elderly. In the course of the fieldwork, I found that the elderly group with mobility problems and crutches were on the high side, and from 15:04 to 16:10, a total of five elderly people were on crutches. One of them used an umbrella as a crutch. And these elderly people are lively and like to watch others play cards.

A: an elderly woman, slightly fat, crutches, holding a pink plastic bag. After walking for a while, she sat on a stone pier beside her, resting for a long time, watching people play cards; then left, hobbling down the steps, picking up some scraps in front of a garbage can, and returned to the alley.

B: An elderly male, with an umbrella as a crutch and a stooped figure, set out from the southwest gate of Zhongshan Park and went back to the statue in Zhongshan Park to watch people playing cards.

C: An elderly woman, holding a shaped walking stick, sat in front of a store for a long time, laughing and joking with the shopkeeper and the neighbors, speaking Hakka, who asked: ‘How are your teeth?’ C said: ‘Injustice, it’s time to pull them out.’ Another neighbor shouted to him in a distant voice: ‘Come out to play? Want to come over and play?’”

It can be seen that the elderly on crutches are a visible group in the historic district, and the square is an important place for them to live. Therefore, the development of public activity space and the construction of barrier-free facilities for the elderly on crutches in historic districts is an important issue.

(2) Use of dialects

In this study, the author noticed that among the residents, middle-aged and elderly people frequently used dialects for communication, especially in Donggongjie and Qiaotou where there are many old residential areas, and almost everywhere, you can hear the residents talking in Hakka, Hoklo and a little bit of vernacular in a loud voice. Only when dealing with children do they use hard Mandarin to educate them. On the other hand, in the more open areas such as Fuqian Hengjie and Zhongshan Beilu, where there are many tourists and a large number of young people, Mandarin is the main language spoken, and occasionally young people can be heard communicating in Hoklo, in which case the young people tend to be local residents who have developed a more familiar relationship with the shopkeepers and stall owners.

“Not far away, I found the Beimen Street Community Service Center is here, downstairs is a public ‘electric bicycle charging station’, opposite the dense buildings in a small square called ‘happiness station’, there are resting places. There is a rest area. I sat here for about half an hour and observed the residents, who spoke mostly dialects and had good neighborly relations. One of the women got off her electric bike and called out to her upstairs neighbor in Mandarin: ‘××, throw a mask down for me. I forgot to bring it.’”

“As I was walking through the alley, I was greeted by an old woman speaking loudly on the phone in Hoklo, and what I could vaguely hear was ‘Take the No. 17 bus, you can go to a good place to drink tea. I used to go to Boro to drink tea’. The street sign in the alley was replaced by ‘Donggong Boundary’, the sound of lunch dishes was vaguely heard from the households on both sides, children were playing around, old people were lecturing their children in raw Mandarin, and there were muffled voices coming from the TV.”

“On the side of a snack street, a young male climbs into a conversation with the boss’s wife. The boss’s wife asked in Mandarin, ‘Where are you from?’ The male replied in Hakka: ‘I’m from Shaoguan, which also speaks Hakka.’”

The use of dialects is both a manifestation of close neighborhood relations and a bond that holds them together.

(3) Utilization of space

Residents of Beimen Street’s use of space reflects the strategies they employ in their daily lives. This study concludes that door-side utilization and first-floor openness are the main strategies adopted by residents in their daily living in the historic district.

“Doorside” is a local dialect concept that refers to the space near the entrance of a home or store, either a small section of sidewalk in front of a store or a small platform near the entrance of a self-built building. The researcher observed that many stores would consciously utilize the doorway side, either by setting up a table, drinking tea and chatting, or by drying and pickling their own harvested radishes. This demonstrates the local people’s need for outdoor interaction and activities, while reflecting the local people’s ability to realize their own needs.

“In front of the stores on either side of the south side, many shopkeepers like to set out a table on the sidewalk and invite old friends for tea, coming and going without thinking.”

“A large number of the buildings in the historic district are single-family homes, built by local residents. Except for the buildings that were opened into stores on the first floor, most of the first-floor residences were living areas, and when you open the door and go in, it is the hall area for making friends. In this walk-through study, in the densely populated areas along Qiaotou, Donggong Street, Court Street and Beimen Street, many residents tended to leave their sturdy doors open, as well as their windows, and there was often the sound of conversations inside the dwellings, with the majority of the occupants being middle-aged and elderly groups.”

“Continuing towards Beimen Street, there is a rather old-fashioned compound, all with more imposing gates, called ‘Miao House’, occupying several old buildings on both sides of the lane street. The residents of this place, like the previous residents of Qiaotou, had the doors of the 1st floor open and welcoming guests, with the sounds of cooking and playing mahjong coming from them, and most of the people around them spoke Hakka.”

It can be seen that the “use of the door” and the “opening of the first floor” are both manifestations of the residents’ maintenance of neighborhood relations, and they also illustrate that among the middle-aged and old-aged groups in Beimenjie Street, neighborhood relations are close and that the residents are actively maintaining neighborhood relations by opening up the space for activities in their daily lives. The residents are active in maintaining neighborhood relations by developing activity spaces in their daily lives.

(4) Traces of agriculture

In the process of urbanization around the world, agriculture has never disappeared from cities, even in New York, the most urbanized city in the United States, residents have also opened up a form of “rooftop agriculture”. Yi-fu Tuan believes that with the acceleration of urbanization and agriculture becoming rare in cities, the desire for agriculture is a romantic expression (Tuan, 2014, 121-122).

This study found residents growing their own vegetables, or carrying out related agricultural activities in a number of places (see Figure 3), and in Beimen Street, although agriculture is no longer mainstream with urbanization, it nevertheless still occupies a place in the residents’ daily range of activities.

Figure 3. Agricultural activities on Beimen Street, Daocheng Lin, 2022.

The process of regeneration of historic districts is often a top-down process. In the process of large-scale development, the authenticity of historic districts is easily destroyed and historic buildings are replaced by “fake monuments” (Yang, 2021). The renewal process of the historic districts in Huizhou City is considered to have the problems of “lack of vitality, commercial hazards, vacancy hazards and lack of traces of life”. However, in the course of the walking study, the researcher found that the local residents of Beimenjie actively used daily life strategies to maintain their original social relationships and lifestyles, and actively absorbed and dialogued with the large-scale regeneration activities, which contributed to the commercial vitality of Beimenjie as a historic district. This paper argues that in the process of renewal of historic districts, space should be given to the daily life practices of local residents, and more detailed research should be conducted on the daily activities of the local residents, so as to obtain a more human-centered community renewal plan.

iv. Conclusion

‘Miscellany’ – the theme of Beimen Street Direct: Addressing the RQ1 and RQ2, we investigated how top-down state-led policies shape the miscellany of Beimen Street’s places, and how residents use miscellany as a strategy to fulfill their needs of everyday life in the street space. An examination of the places, daily life strategies, and community culture of Beimen Street reveals that “miscellany” is one of the main threads of Beimen Street. The mixture is reflected in the three levels of time, behavior, and culture.

In time, the architectural styles and building components of Beimen Street have been hybridized, such as the replacement of buildings from the Qing Dynasty with modern iron gates because the traditional courtyard gates had fallen into disrepair (see Figure 4); and the establishment of tin stores on the courtyard walls in the course of community renewal, all of which have created a mix visual style and place identity (see Figure 3).

Figure 4. Mixed architectural styles of Beimen Street, Daocheng Lin, 2022

Behaviorally, the residents of Beimen Street tend to have a miscellaneous orientation in their daily activities. For example, in the operation of stores, the logic is often not based on the type of store or a regimented business plan, but rather on the needs of the neighborhood and their own agricultural products, and in the strategies of daily life, the residents don’t really care about the actual use of things but rather prefer to make use of the doorways to fulfill their own needs. Thus, miscellany is also a verb in historic districts.

At the cultural level, “miscellany” often means the hybridization of cultural symbols and actions. As mentioned above, Beimen Street is rich in cultural symbols, and these cultural symbols are often in dialogue with each other, whether intentionally or not, to create new meanings, and thus a certain degree of vitality.

In conclusion, this paper argues that miscellany is an important theme of Beimen Street and that the characteristics and actions of hybridization also enable Beimen Street to maintain its vitality and characteristics, which gives Beimen Street the typical charm of a historic district.

Reference

Borer, M. I. (2006). The Location of Culture: The Urban Culturalist Perspective. City & Community, 5(2), 173–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6040.2006.00168.x

Butler, G., Szili, G., & Huang, H. (2022). Cultural heritage tourism development in Panyu District, Guangzhou: Community perspectives on pride and preservation, and concerns for the future. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 17(1), 56–73.

Certeau, M. de. (2011). The Practice of Everyday Life (S. Rendall, Trans.; 3rd ed.).

Chen X. H. (2014). Richang shenghuo shijiao xia jiuchengfuxing sheji celue yanjiu [Research of Old City Regeneration Design Strategy Based on Everyday Life]. Doctoral Thesis, South China University of Technology.

Cho, K. Y., Kusumo, C. M. L., Tan, K. K. H., & Rasoolimanesh, S. M. (2022). A systematic review of indicators for sustainability of urban heritage sites. Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research, ahead-of-print.

Fan, X. (2020). Research on the Reconstruction and Reuse of Historic Blocks From the Perspective of Urban Catalysts: Taking a Historical District of Foshan as an Example. 449–455. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.200923.077

Gauthier, H. L., & Taaffe, E. J. (2002). Three 20th Century “Revolutions” in American Geography. Urban Geography, 23(6), 503–527.

Guo Y. M. (2014). Kaoxian de faxian: zaixian richang de xiansuo [Finding Modernology: The Clue of Ordinary Represented]. Architecturer, 05, 6–20.

Gong, W. X. & Zhong, X. J. (2015). Huizhoushi lishiwenhua jiqu jianjinshi gengxin celue [Progressive Renovation Of Huizhou Historical District]. Planners, 31(01), 66–70.

Hägerstrand, T. (1985). Time-geography: Focus on the corporeality of man, society and environment. The Science and Praxis of Complexity, 3, 193–216.

Huang, L. (2020). Research on the Morphological Characteristics and Causes of Pinzijie Historic District in Foshan [Doctor of Philosophy, 华南理工大学]. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CDFD&dbname=CDFDTEMP&filename=1021546287.nh&v=

Huizhou Historic Districts Convervation Office. (2017a). Beimen zhijie lishi wenhuajjiequ baohu xiangxi guihua [The detail plan for conservation of Beimen Street]. http://zjj.huizhou.gov.cn/lswhmcbh/bhgh/content/post_24139.html

Huizhou Historic Districts Convervation Office. (2017b). Huizhoushi lishi jianzhu yilanbiao. http://zjj.huizhou.gov.cn/lswhmcbh/bhml/content/post_24152.html

Jiang, B., An, X., & Chen, Z. (2022). Understand space–time accessibility using a visual metaphor: A case study in Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macao Belt. Environmental Earth Sciences, 81(4), 1–9.

Li H. (2010). Chengshi kongjian kuozhanzhong shidi nongmin zhonglou de lixing yu weiquan: cong woshoulou jingguan dao nongmin xiaoji yingdui chengzhongcun gaizao de ge’an yanjiu [Lost Land PeasantsʾRationality of Building Planting and Their Right Protection During Urban Space Expansion]. Journal of Northwest Normal University (Social Sciences), 47(5), 9–15.

Lin, C., Yang, Y., Tang, Z., Li, F., & Li, W. (2014). Dynamic Conservation of Historical District in Huizhou City. Journal of Huizhou University, 34(05), 33–37.

Luminais, M. (2015). Walking in the European City: Quotidian Mobility and Urban Ethnography edited by Timothy Shortell and Evrick Brown. International Social Science Review, 91(1), 1–2.

Mai, Y. X., Yang, C. H., You, K. X., Xu, J. Q., & Hao, X. F. (2021). Wenchuang+ lishijiequ kongjianshengchan de xitong donglixue jizhi [The system dynamics mechanism of space production in the “cultural creativity plus” historical district: A case study of Zhuhai Beishan Community]. Geographical Research, 40(02), 446–461.

O’Neill, M., & Roberts, B. (2019). Walking Methods: Research on the Move. Routledge.

Pink, S. (2021). Engaging architectural anthropology. Architectural Anthropology: Exploring Lived Space, 219.

Pink, S., Hubbard, P., O’Neill, M., & Radley, A. (2010). Walking across disciplines: From ethnography to arts practice. Visual Studies, 25(1), 1–7.

Shortell, T., & Brown, E. (2016). Walking in the European City: Quotidian Mobility and Urban Ethnography. Routledge.

Stender, M., Bech-Danielsen, C., & Hagen, A. L. (2021). Architectural Anthropology: Exploring Lived Space. Routledge.

Tuan, Y.-F. (2001). Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience (Reprint edition). Univ Of Minnesota Press.

Tuan, Y.-F. (2014). Romantic Geography: In Search of the Sublime Landscape (1st edition). University of Wisconsin Press.

Wang, W., Ou X. Q., & Xu, H. H. (2018). Lishijiequ de tuxiangxushi yu zaixian: Huichangsha Taipingjie de chuangzuo yu sikao [Image Narration and Reproduction of Historical Blocks: The Creation and Reflection of Painted Changsha Taiping Street]. Zhuangshi, 07, 118–120.

Yang, Z. (2021). Destructive reconstruction in China: Interpreting authenticity in the Shuidong Reconstruction Project, Huizhou, Guangdong Province. Built Heritage, 5(1), 15.

Yi’En, C. (2014). Telling Stories of the City: Walking Ethnography, Affective Materialities, and Mobile Encounters. Space and Culture, 17(3), 211–223.

Zhang, A.Y., Roast, A & Morris, C (2022) Wanghong Urbanism: Towards a New Urban-Digital Spectacle.Mediapolis Journal, 7(4), https://www.mediapolisjournal.com/2022/11/wanghong-urbanism/

Zhang, Z., & Liu, W.R. (2019). Richangshenghuo shijiao xia beijing dongsi lishijiequ baohu he gengxin [The conservation and renewal of historical blocks in Beijing’s Dongsi area from the perspective of daily life. Industrial Architecture, 49(03), 63–70.

Zhang, X. Y, Wang, S.F., & Fei, Y. (2017). Keshishi de Weigaizao: Lishijiequ de huohuatisheng celue tantao [The Implementable “Micro-Reform”: A Strategy for Activating Historic Districts]. South Architecture, 5, 56–60.

Zhang, Y., & Chai Y.W. (2016). Xin shijian dilixue: ruidian Kajsa tuandui de chuangxinyanjiu [“New” time-geography: a review of recent progress of time- geographical researches from Kajsa Elleard in Sweden]. Human Geography, 31(5), 19-24+46.

Leave a Reply